Are you ready for jaw-dropping views and an unforgettable adventure? Meteora is otherworldly, and it was definitely one of the highlights of our trip! Until we began travel planning, I was not even aware Meteora existed. As one of Greece’s most visited attractions, find a way to get to this remote area! My photographs just don’t do it justice.

Rising from the plains of Thessaly with a view of the Pindos Mountains, Meteora comes complete with grand rock formations and an ancient complex of Byzantine monasteries. It’s unique; you won’t find the ocean, iconic blue-domed churches or one single Greek temple.

The city of rocks is a paradise for nature lovers, hikers, climbers, photographers, bird watchers, and anyone interested in history or holy places. Even if you never visit one mountaintop monastery, go for the breathtaking views!

In 1998, it was listed on UNESCO’s World Cultural and Natural Heritage list. Natura 2000 also includes Meteora in their European network of nature protected areas.

Meteora’s name is fitting. The Greek word “meteoros” means “suspended in the air.” Although Greek mythology tells us the rocks were formed by meteors being hurled to the earth by an angry god, they most likely came about from centuries of geological tectonic forces and weathering from nature, water, wind, and river erosion.

Even though resident monks are annoyed by the attention, one of the world’s best kept secrets got out when Meteora became a filming location for the James Bond movie “For Your Eyes Only.” Awareness ramped-up even more when the “Game of Thrones” series filmed scenery in Meteora for the fictional castle of Eyrie (part of the House of Arryn).

The James Bond movie “For Your Eyes Only” was filmed at the Holy Trinity Monastery.

Why did monks go to Meteora?

After Mount Athos, Meteora is the second largest monastic center in Greece. In the 11th century, a small group of ascetics and hermit monks, called Meteorites, made their way to this area seeking spiritual reflection and solitude.

Like a bird’s nest, monks built their homes and lived in caves and fissures in the steep cliffs, some as high as 1,900 feet. They rock climbed and also used long hand-made ladders, which could be hauled up if they ever felt threatened.

In the 12th century, area hermit monks established a central chapel and formed the Skete of Doupiani (what we might today call an RMO – a resident monk association).

That chapel, the Church of Theotokos (Virgin Mary) is the oldest Meteora monument; it still stands today. For several centuries, hermit monks would leave their caves on Sundays and meet for prayer and important Feasts. I bet it was nice to have a little fellowship after a week of isolation.

By the 14th century, the Byzantine Empire was under attack by Turkish incursions. As the Ottomans conquered region after region and persecuted Christians well into the 15th century, fleeing monks continued to find a safe haven up in the rocks. Even before Meteora was protected by Greek law as a sacred place, it was well known as a holy place of refuge.

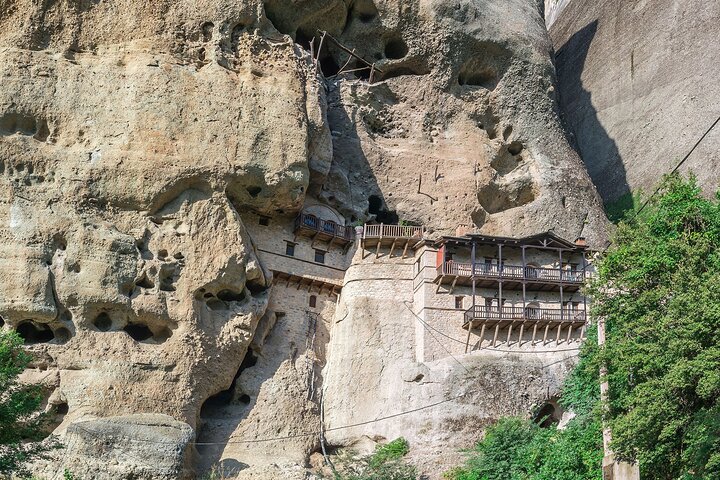

Above and below: The caves and Hermitage of St. Gregory.

You can still see evidence of caves, with ladders left behind, all over Meteora where former hermits lived as recently as the 1900s.

Are you curious like me? How did they survive, especially in the winters? Did they get lonely? Did any monks ever fall and get hurt, or worse? Where did they go to the bathroom? How and what did they eat? I’m guessing no one ever said, “I’ll be right back. I’m running out for milk and bread.”

Early on, Meteora was simply a wilderness of rock pillars. There were no roads, villages or houses, and monks didn’t even want pathways, which led to their caves, to be visible. Access to where they lived was deliberately difficult.

During a period of peace in the 1920s, (900 years after the first monks arrived), convenient roads were built from the town of Kalambaka to monastery sites. Pathways became rock walkways, and steps were chiseled into rocks for somewhat easier access.

Look up! The Holy Monastery of Great Meteoron is perched cliff-top!

The earliest monastery was established by St. Athanasios, a monk from Mount Athos in Halkidiki who was fleeing Turkish pirates. He was the first to climb the steep pillar known as “broad rock” in 1343. He built a few cells in caves, created a chapel, and then constructed a small hermitage.

The cave where he lived can still be seen today near the entrance to what evolved into his vision: the largest monastery on the highest peak – the Great Meteoron Monastery.

Facing danger and persecution, monks kept climbing to higher rock pillars using ropes, stakes, and primitive ladders. By the 15th century, a total of 26 monasteries and 15 hermitages had been established. Most were funded by Byzantine emperors, then constructed and managed by ascetic monks.

Of the 26 monasteries, only six monasteries (two of which are run by nuns) still exist and can be visited in Meteora today. They are:

- St. Nicholas Anapausas Holy Monastery

- Great Meteoron Holy Monastery (or Transfiguration)

- Varlaam Holy Monastery (All Saints)

- Rousanou Holy Monastery

- St. Stephen Holy Monastery

- Holy Trinity Monastery

How in the world did they build on top of a mountain?

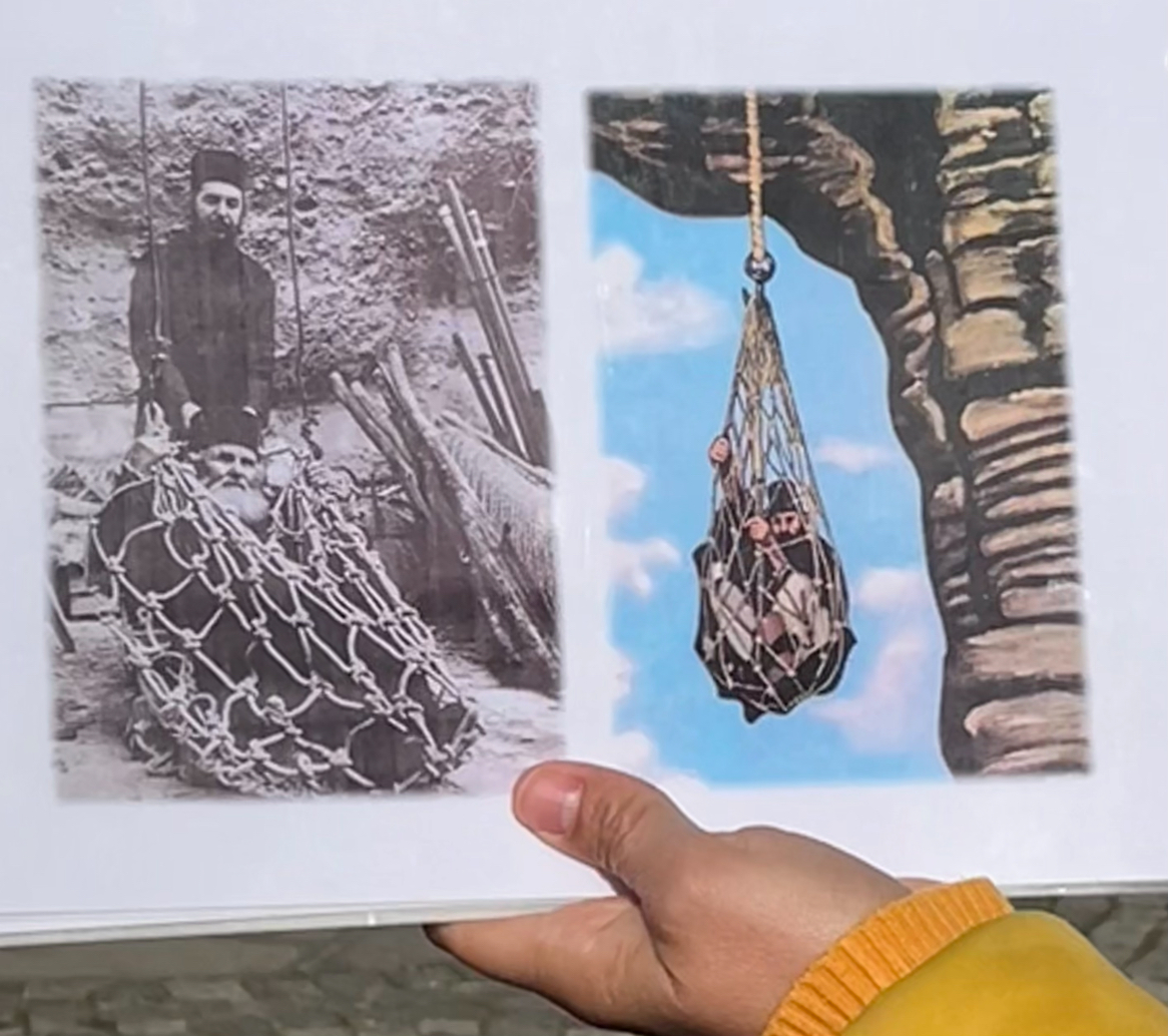

The answer is: the hard way. With backbreaking work, sacrifice, and divine intervention, the monasteries took years to build using primitive tools and ingenuity. Monks originally hoisted all materials, including heavy stone, to the top using removable ladders, crude scaffolding, and nets.

I can’t help but point out those scary ladders!

For centuries, the rope, net, and ladder method was also the only way for monks to enter a monastery. The goal was to permanently keep invaders from reaching the top.

Eventually, they invented their own version of a windlass: a man-powered pulley to lift monks, construction materials, and anything needed at the monasteries. Our Meteora guide, Katerina, told us the monks had great faith. They never replaced a rope or net. . . until it broke. Yikes!

Photos from our Metora guide and from the Holy Trinity Monastery – ropes, nets and hooks

Ready to see for yourself?

Do some planning before arriving in Meteora. You can reach it by car, train, or bus if you’re not on a planned tour. We had a rental car. It’s about 5 hours north of Athens and 4 hours south of Thessaloniki.

Meteora is stunning any time of the year. April, May, September and October claim to be the best months to visit, yet many prefer to be there in winter season (even in the snow) with very few tourists. It’s best to avoid the summer due to extreme heat and maximum overcrowding, but GO if it’s the only time you can visit.

We traveled to Meteora in late-March. What Greece considers the “winter season” was perfect for our group of four. Temps were in the 60° range with absolutely no crowds!

We climbed to and visited four monasteries all in one day (two with a Meteora tour guide and two on our own). Two monasteries were sadly closed that day. Honestly, I don’t know if we could have done all the climbing in one day if it had been hot. And, Disclosure: I had fallen and broken my tailbone in Santorini seven days before.

Superb garden view from the Holy Monastery of Varlaam

Originally, we devoted a firm “one day” for exploring Meteora with an overnight stay. Thankfully, friends who had recently visited encouraged us to stay at least two nights and another day. We couldn’t add an extra day, but we did spend two nights, which gave us one more sunset and a nice respite from our road trip.

Travelers obviously visit Meteora to see the monasteries, but hiking, rock climbing, sunset and hermit cave tours are popular too. Rock climbers travel from all over the world to scale the mighty pillars.

Two options for where to stay: The main town of Kalambaka sits down below Meteora with nice hotels, family-owned Greek restaurants, souvenir shops, groceries, and night life. It’s a good fit for big tour groups and buses, and it provides edge of Meteora views 24/7 with rocks lit up at night.

A sneak peek of Kalambaka between rocks as we were climbing up to a monastery.

Nestled up higher at the base of the rocks, tiny Kastraki village is just minutes from the monasteries. Kastraki also has amazing views, hotels, tavernas, plus an extensive network of trails connecting from the village to various rocks and monasteries.

Our two-night home base for exploring Meteora was at Hotel Doupiani House in Kastraki. With panoramic views of the rocks, it’s located at the top of the village, just off the road heading into Meteora. It’s about as close to the monasteries as you can get and a great home base for hikers and climbers.

Early morning view from our balcony in Kastriki village at the Hotel Doupiani House.

We had a second-floor balcony room at the hotel overlooking the garden and patio. . . and of course, those views! Service was friendly, and the rooms were large and nice. They have a bar where they serve wine from their vineyards.

Breakfast was delicious! The sweet lady who prepared “quite the spread” each morning explained our options, the majority of which were homegrown and prepared right on the property from their gardens and fruit trees (fresh yogurt, jams, savory Spanakopita, etc.).

Hotel Doupiani House came highly recommended from friends who had stayed there months before. Make sure to book a room on the side with rock views. It’s a special place! ⇒http://www.doupianihouse.gr

Hotel Doupiani House – the outdoor patio, grounds, and vineyard view from our balcony.

What’s next? Stay tuned for my upcoming travel blog about visiting the Meteora monasteries.

https://traveltipsbytami.com/meteora-monasteries-a-climb-to-the-top/

It’s not just about the incredible buildings; it’s about the adventure you’ll have getting to them! I’ll give you tips on the strict dress code, admission prices, days of operation and opening hours for all six monasteries… plus the secret spots for sunset/sunrise pics!

Come and see what you’re missing in Meteora! It’s worth the climb!

Until then, keep exploring!

Check out my other Greece series travel blogs:

Santorini, Greece – Off the Beaten Path

Athens, Greece – The Acropolis

Olympia, Greece – The Birthplace of the Olympics

Delphi, Greece – It’s Still a Mystery

For all travel blogs, visit my blogsite: https://traveltipsbytami.com

While a couple of the monasteries are easily accessible from the parking area, do not pass up the others. The climb can look and is challenging but well worth the effort. It is amazing to see how these monks adapted to living high on these rock formations. The views are breath taking.