Every two years, more than 200 countries come together to compete in a global, multi-sport, athletic competition known as the modern Olympic Games. Where did it all begin? Put your toe at the starting block, and let’s go visit ancient Olympia, Greece!

Citius. Altius. Fortius --- Faster. Higher. Stronger

Olympia’s story is much more than an archaeology site of athletic facility and temple ruins. It’s the birthplace of the Olympic Games and a UNESCO World Heritage site. Visitors from all over the world trek out to this small Greek town to see where the first sports competitions began.

You probably won’t happen upon secluded Olympia by accident. The western Peloponnese area is a good 4-to-5 driving hours from Athens, and most visitors arrive on a tour bus or cruise ship excursion.

After leaving Athens and a quick stop at the Corinth Canal, Olympia was our first landing place on a 1650-mile driving journey across Greece.

TIP: Confirm seasonal business hours. We visited in March considered “winter season,” so the site was open from 8 am to 3 pm, plus half price, with very few visitors. It was lovely!

The ancient site is not far from the town now called Olympia in a beautiful valley below Mount Kronios, where the Alpheios and Kladeos Rivers meet. We found the sanctuary in spring bloom with wild flowers!

A lawnmower had not yet touched the grounds!

Why were they here?

Olympia began as a local religious festival to honor Zeus, king of the mythical gods and Hera, Zeus’ wife (and oddly, his older sister). For the most part, it was all about Zeus. It started as a walled pilgrimage site called Altis with temples, statues, and altars for sacrifices. It was not a town, and no one ever lived at the site.

It evolved into the most significant sanctuary and athletic center in Greece, and it lasted for over 1,200 years. More than 45,000 Grecian males would gather every four years to honor Zeus at a festival which included athletic events. Its purpose was to enrich the Greek culture, to educate and strengthen the military, and to unify the independent Greek city-states who were always fighting each other.

Games in Olympia were banned in 394 AD by Theodosius, the Christian Roman Emperor, who commanded all pagan activities to stop. His successor renewed the games, but in 520 AD, Justin I officially forbid all pagan activities in Greece. Olympia was further destroyed by a tsunami, earthquakes and mudslides. The modern Olympic Games did not begin until 1896.

Let the games begin. . .

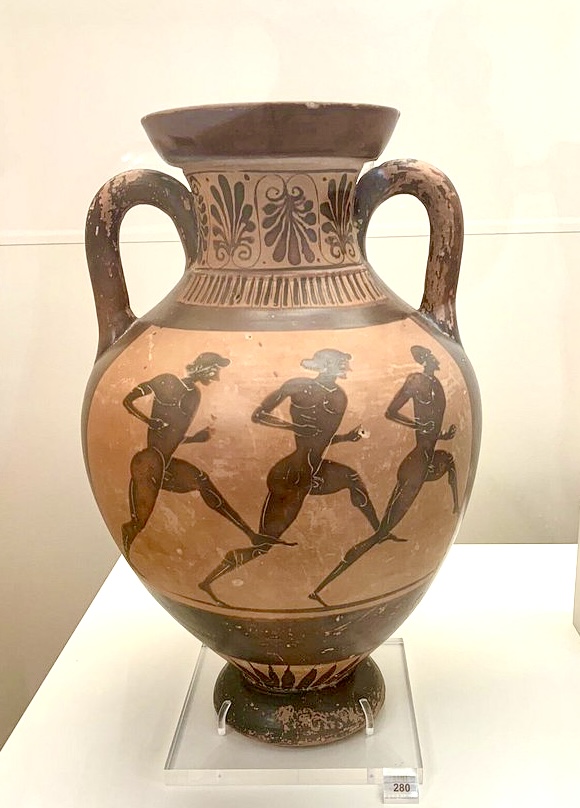

The first recorded Olympic games were in 776 BC, although many believe they’d been organized for years. Until the Romans came along, only Greek-born athletes could participate. The first 13 games had only one event: a running competition. As events were added, the games eventually lasted five days.

To promote good will, a sacred peace truce was enforced. All fighting, battles, and military activities would cease (stop) for one month so athletes, coaches, and spectators could travel safely to Olympia and participate.

While the games in Olympia were the most revered, they were part of a four-year cycle of Panhellenic Games known as an Olympiad. Games were scheduled so athletes could participate in at least one event every year at major sanctuaries. The games were so important and influential, the Greek calendar system was created by historians who measured time by the four-year Olympiad game schedule.

Games in Olympia took place in “year one” of the cycle. Every two years, the Isthmian games, (near Corinth) and the Nemean games (in Nemea), occurred. In the third year cycle, the Pythian games were held in Delphi.

Who Competed?

Olympic athletes were males only: men and boys who competed separately. Women didn’t compete in Olympic events until the Paris Games in 1900.

Both sports and military training were important for every Greek male. They believed a healthy and strong body, plus physical beauty, would please the gods. Cities supported their most important athletes who, from childhood, were given special treatment and diets, trainers, and strict training regimens.

The Gymnasium and Palaestra

In ancient Greece, the school and training area for competitions was called the Gymnasion. The Romans changed the spelling to Gymnasium. The Greek word “gymnos” means naked, and athletes trained and competed in the nude. Athletes arrived a month before the Olympics to train.

A portion of the Gymnasium is still being excavated.

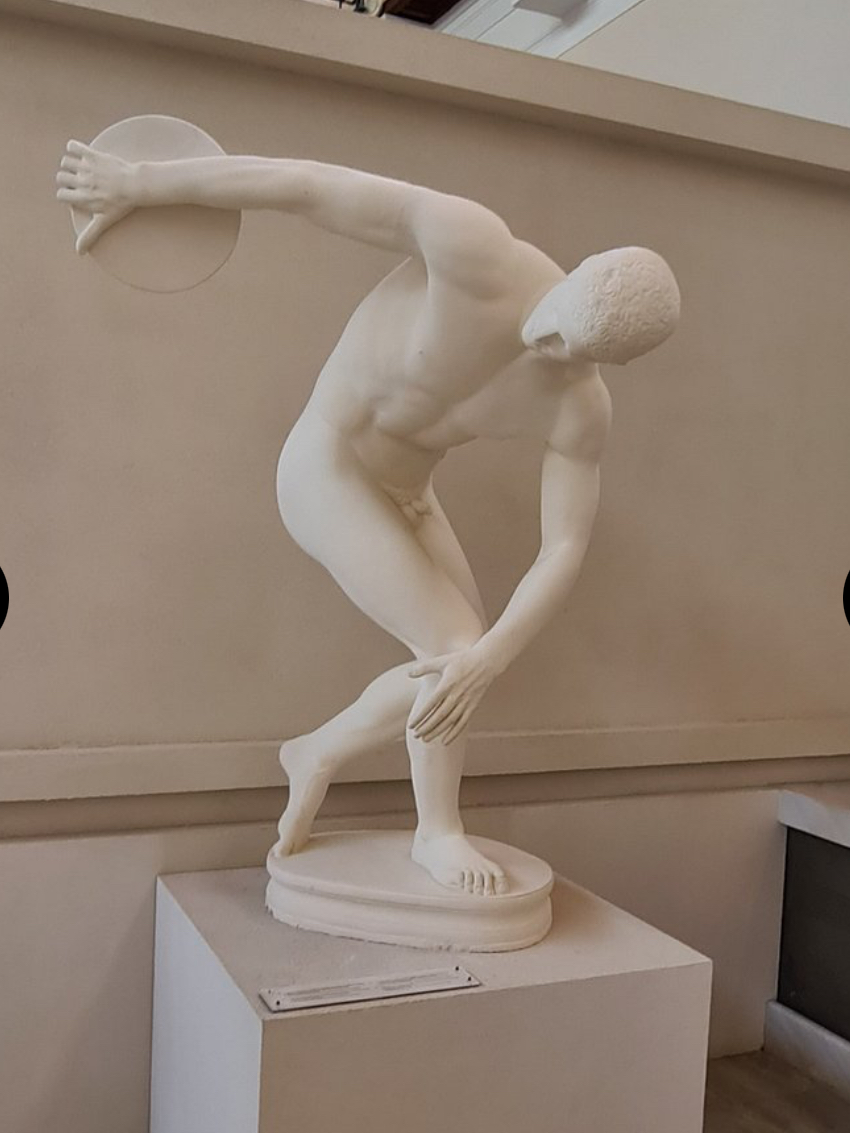

Built in the early 2nd century BC, athletes trained at the gymnasium for events requiring a large amount of space. The rectangular practice field (built the same size as the Olympic Stadium) was perfect for discus, javelin and sprint/running practice.

It was surrounded on all four sides by columned and covered walkways known as stoas. Trainers and spectators could watch from the shade. There was no “sideline parenting” from moms!

Part of the gymnasium complex was a wrestling school called the Palaestra. This square area was built in the 3rd century BC and was used for combat sports like boxing, wrestling, and pankration. The Palaestra was also surrounded by covered stoas and had special rooms for adding oil and powdering bodies with dust/sand, baths, as well as lecture classrooms.

Wrestling is a word derived from the Greek palé. Pankration was an unarmed total combat sport taken ‘to the max’ with a combination of boxing and wrestling. It’s similar to today’s modern mixed martial arts and ultimate fighting. Some even died in Panraktion events.

The Wrestling School

On your mark, get set, GO!

Through this stone archway is the world’s first stadium. The tunnel into the stadium (built in 300 BC) was called the krypti. What we see today is actually the third stadium. This particular track was shifted a little to this location during the end of the 6th century BC.

Can you imagine the thrill of athletes running out of the stone tunnel to the roar of 45,000 fans?

The Greek word “stadion” was not only the building or area in which it took place, it was a unit of length consisting of 600 ancient Olympic Greek feet. In Olympia, the racetrack markers were 192.27 meters apart. If it doesn’t “add up” for you (around 630 feet), just know that “feet” were actually all different sizes. teeheehee

Spectators sat and watched from the grassy banks on each side of the track. Judges had box seats, which still survive (shown on the right). Slaves and women had to watch from outside on the Hill of Kronios.

It's not a marathon, it's a sprint!

Runners did not run around an oval track. They ran up, and sometimes back, on a rectangular clay track. And, they ran barefoot; no one had NIL or famous “shoe” company contracts.

At first, the games featured just one test of speed: a stadia sprint from one end of the track to the other (a 200-meter foot race). The first Olympic Champion in 776 BC was a cook named Coroebus who won the only event, the stade foot race. In 2004, it was the venue for the Shot Put event in the Athens Olympics.

The diaulos was added (2 stadion or a 400-meter foot race) along with a dolichos (a long-distance run which ranged between seven and 24 stadion or 1,344-meters to 4,608-meters, or approx. a 5K). Finally, the Greeks had a grueling, sheer strength race called a hoplitodromos (a 400 or 800-meter foot race) where athletes ran in full, heavy armor (12 pounds) and carried a shield.

With 12 starting gates, the stone start and finish lines also still survive at each end of the track.

South of the stadium, Olympia once had a Hippodrome for horse and chariot races. It hasn’t been excavated because river flooding washed away the venue.

So, did they ever run a marathon in ancient Olympia? No. In the modern Olympics, the men’s marathon began in 1896. Women’s marathons were added ninety years later in 1984.

The 26.2 mile modern marathon was inspired by the legend of the Greek messenger, Phidippides, who ran nearly 25 miles (40 kilometers) from Marathon to Athens to announce the Greek victory over the Persians in 490 BC. As the story goes, he promptly collapsed and died. The confirmed marathon distance of 26 miles, 385 yards (26.22 miles) became official after the 1924 Paris Olympics.

Blame and shame Zanes - and the Bouleuterion

Sixteen bronze statues of Zeus lined the pathway to the stadium called Zanes, (the plural of Zeus). Any athlete who disrespected or violated an Olympic game rule was fined by the judges, and the fine money was used to create the statues. Today, only the stone bases remain.

The rule-breaking athlete’s name and offense was etched on the base of the statue causing shame, not only to them, but to their city. As Olympic judges and athletes entered the stadium tunnel, they would spit on names listed on the Zanes.

No one wanted their name on a Zane.

Athletes could be fined for cowardly quitting an event, doping (using forbidden herbs or drinking animal blood), bribing their opponents or judges, and/or failing to train properly. Even in ancient times, official urine testers were used for what they considered doping.

The Bouleuterion, or Council House, was made up of the Olympic Senate members responsible for organizing the games, athletes, umpires, and judges. This is where the athletes registered, drew lots, and where their events were announced.

Both athletes and their trainers swore at the Altar of Oaths not to cheat or commit Olympic game offenses before the statue of Zeus.

Hail to the Victors

The triangular Pedestal of Nike held a statue of the goddess Nike representing victory who overlooked the Winner’s Circle.

The partial statue of Nike (425-450 BC) is now in the Archaeological Museum of Olympia

Winners were announced near the temple entrance at the long Stoa of Echo, or Echo Hall. This stoa was called “Heptaëchos,” because announcements (or any sounds uttered) echoed seven times with amazing acoustics.

Olympic winners were also crowned with a wreath of olive branches at the Winner’s Circle below the statue of Nike. Unlike the modern Olympics, there were no gold, silver, or bronze metals. Olympic winners did become famous and were showered with gifts (like olive oil), advantages and life-long benefits, especially from their hometowns.

Use your imagination to picture the long Echo Stoa.

The Temple and Statue of Zeus

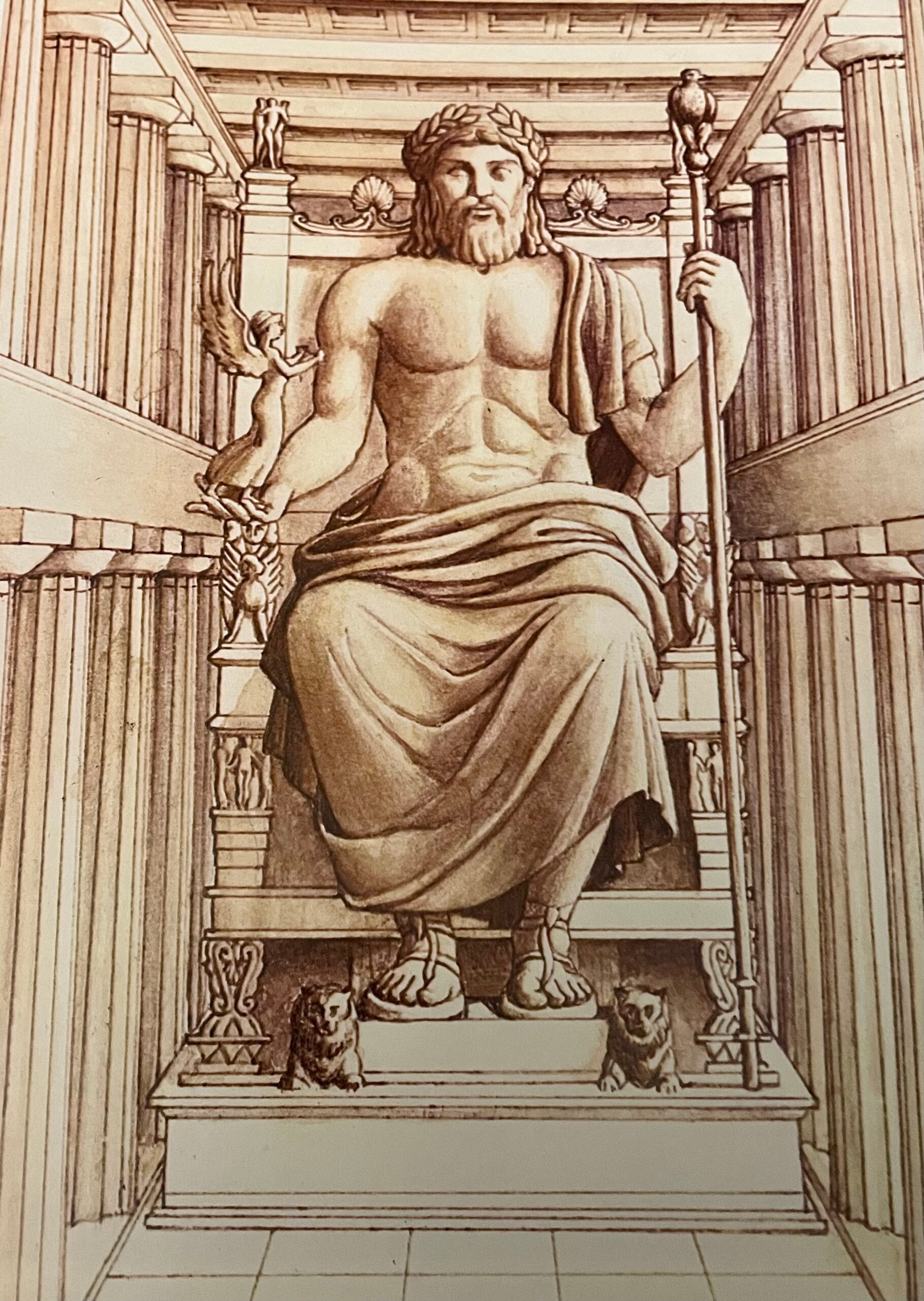

Considered one of the Seven Ancient Wonders of the World, the massive Temple of Zeus dominated the Altis. It now sits in ruins. Zeus was the king of the gods and also served as the patron of the Olympic games. It was the largest Doric temple in the Peloponnese (470-456 BC) created by the architect Libon.

Temple of Zeus remains

Unlike other cities using marble, columns were made from local limestone (seashells and fossils) which weren’t entirely durable. The limestone drums were then covered in a stucco marble-powder to give a marble effect.

Gigantic temple ruins: 2-ton column drums and 12-ton capitals.

Some of the marble sculptures and 12 partially-restored temple metopes (which portray the 12 Labors of Hercules) can be found in the museum.

The main event was the immense chryselephantine statue of Zeus sculpted by Pheidias in 430 BC. The temple stood six stories tall, and the gigantic statue of Zeus sat 40 feet high on a golden throne. It was finished and placed in the temple in 435 BC. Zeus held his scepter in his left hand and a Nike (made of gold and ivory) in his right hand.

Reconstruction of the interior of the Temple of Zeus. 1976 by K. Hermann.

TIP: Chryselephantine means the base (this one made of wood) was covered in gold and ivory. Zeus’s body was covered in ivory; everything else was covered in gold.

You can visit Pheidias’ Workshop where the Greek sculptor built the giant Zeus. It has been located near the temple and excavated.

Other noteworthy monuments and areas

The fountain and aqueduct supplying all of Olympia with fresh spring water during the Roman era was called the Nymphaeum. Built in 150 AD, the curved fountain with two tiers of statues was built by the wealthy Roman banker, Herodes Atticus (also responsible for the Athens Odeon to honor his wife). Zeus was the main statue, along with Roman emperors and the Atticus family.

The remains of the Nymphaeum statues, and a bull which was a part of the fountain, can be seen in the Olympia Archaeology Museum.

The Philippeion was built as a circular Ionic 18-column memorial to King Philip II of Macedon and his family (finished by his son, Alexander the Great). It was dedicated by Philip to Zeus to celebrate his victory at Chaironeia in 338 BC.

The Philippeion (336 BC)

Also west of the Altis and separated by the Sacred Road are the Greek baths and a swimming pool, the Roman hot baths, the Theokoleon (priests’ residence), the Leonidaion (officials’ quarters), and the Roman hostels.

South of the former Hippodrome is a group of mansions and baths, including the famous house of Nero, built by the emperor for his stay and participation in the Olympic games.

Every Olympic Flame still begins at the Temple of Hera Altar

The ancient site’s oldest temple (late 7th century BC), and one of the oldest monuments in Greece, is the Doric Temple of Hera or Heraion. It was first built of wood, then replaced by stone in honor of Zeus’s wife, Hera.

The Temple of Hera

The Greeks eventually held a festival with female games to honor the goddess Hera as early as the 6th century BC. Separate from the Olympic games, only unmarried women could compete in the Heraean Games, which were mainly foot races.

Every Olympic torch and flame today is ignited right here at the altar in front of the ruins of the Temple of Hera.

Weeks or months before the Olympics’ opening ceremony, a group of women (the Vestal Virgins) perform a celebration at the Temple of Hera. A fire is kindled by the light of the sun using a parabolic mirror. That fire lights the first torch of the Olympic Torch Relay which goes from Olympia to Athens and then to the country hosting the next Olympics.

That flame lights the Olympic cauldron during each opening ceremony. Typically, a famous athlete from the hosting nation is the last runner in the Olympic torch relay. And what if the flame goes out? Back-up flames from the original ceremony are always available should a torch–or even the Olympic cauldron–lose its flame.

The 2024 Summer Olympic Rings in front of Paris’ Hotel-de-Ville (City Hall) from my 2022 France trip.

The torch for the Paris 2024 Olympics was lit by the sun’s rays at this site in Olympia on April 16, 2024. The Olympic flame for the Milan/Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics will be lit on November 26, 2025 in Olympia. The countdown has begun!

Don't Skip the Museum!

The Archaeological Museum of Olympia has been on this site since 1888 but was rebuilt after the 1954 earthquakes. Your site ticket includes entrance into the museum. You might visit here first for perspective and check out the reconstructed model of the ancient site.

Each room has priceless works on view, but the most impressive are the gallery and pediment sculptures from the Temple of Zeus, the Nike of Victory (shown earlier), and the Hermes of Praxiteles.

Hermes and the Infant Dionysus (340-330 BC) by Praxiteles- Discovered in the Temple of Hera in 1877 is a rare seven-foot statue of Hermes carrying the infant Dionysus to his nurses to protect him from the wrath of Hera.

The Gallery of Sculptures from the Temple of Zeus – The East Pediment

The West Temple Pediment Sculptures

Very few examples of monumental sculptures survive from the 480-450 BC period. Not only does Olympia have 42 impressive figures from the the east and west pediments, this room includes 12 temple metopes in good condition.

Close-up of Apollo from the West Pediment

A terrracotta statue depicting Zeus and Ganymede (480-470 BC). Zeus carries the son of the King of Troy to Olympus where the gods would make him their cupbearer and give Ganymede the gift of eternal youth.

Olympia has one of the largest collections of ancient weapons. Zeus not only presided over the Games; he presided over battles. Gifts to Zeus included booty taken from historical events and victories. Corinthian bronze helmets, votive offerings, figurines, tripods, weapons, pottery, and armory can be seen throughout the museum.

This terracotta sun sphere crowned the roof (the Acroterian or “summit”) of the Herarion (7th century BC). It was placed at the highest point of the temple to look like the sun and symbolized Hera’s shining glory.

When you don't know what you don't know...

TIP: Not on a planned tour? We secured a private small-group reservation (for the four of us) with Niki Vlachou, a phenomenal local Olympia guide.

Believe me, I do my research, but Niki brought the ancient site to life and has so much passion and patriotism for her country! We left educated and with a great appreciation of not only Olympia and its history, but Greece. I highly suggest Niki for guide opportunities for both Olympia and Athens! [email protected] (697) 242-6065 http://www.olympictours.gr

TIP: If you rent a car anywhere in Greece, you’ll need to get an International Driver’s Permit (IDP) before you go. We secured our permits at AAA Travel, one of only two private entities in the US authorized by the U.S. Department of State (AATA is the other). With your valid driver’s license and $20, you’ll be driver permit ready in minutes. And don’t forget travel insurance! http://www.aaa.com

Our husbands, who fearlessly drove us across memorable Greece!

****

What’s next? We head to Mt. Parnassus and the ancient religious sanctuary of Delphi, Greece!

Until then, keep exploring!

For other travel blogs, visit my blogsite: https://traveltipsbytami.com

Tami Kooch

This was so entertaining and educational! It’s sad that more of the statuary didn’t survive.

The Roman Christians did their best to destroy it when they outlawed paganism. Then the earthquakes. The flooding and mud slides may have preserved what was left. The archaeology teams are still at it! It is a fascinating story though.

What an amazing experience where it all began. I can now say I have crossed the Olympic starting line while at the stadium. Niki provided great detail and background as well. Thanks to Tami for researching and booking her for our visit. Olympia is not the easiest place to get to but definitely not one to miss.

Agree Agree! Loved Niki too; if only we could have taken her along with us on our journey.